Egg

by Michele Stepto

There was once a woman called Lillian who had an only child, a son, whom she loved very much. As long as the boy was little, everything went well, but as he grew older he began to wander further and further from home, and when he reached manhood he entered a line of business that took him often to other lands. Lillian, who was a wise woman, contented herself with the many letters he wrote describing the places he had seen in his travels. In them, she learned of the existence of a bay whose waters were always amethyst, of a hidden plaza of flower-strewn, wooden balconies, that had no way in or out, of a palace of one thousand rooms in which no one had lived for a thousand years. These letters she kept in a large, beautiful box, carefully ordered, on a shelf in the room her son had used as a boy, and as the years went by the box became fuller and fuller, until Lillian began to think that she would soon need a larger box, or another one.

One day, the messenger who brought her the letters from her son appeared at the door carrying a small, brass urn. Pasted on the side of it was a paper bearing an official stamp and stating that the contents were all that remained of her son, who had died some weeks earlier in a distant city. Lillian did not then (nor did she ever afterwards) look inside the urn. Instead, she placed it on the shelf next to the box of letters, and as she did so she felt all her wisdom desert her. Perhaps it isn’t true, she told herself, but then she remembered that she had not had a letter from her son in many weeks, and she knew that what she had now, the box of letters and the brass urn, were all she would ever have of him in the long future.

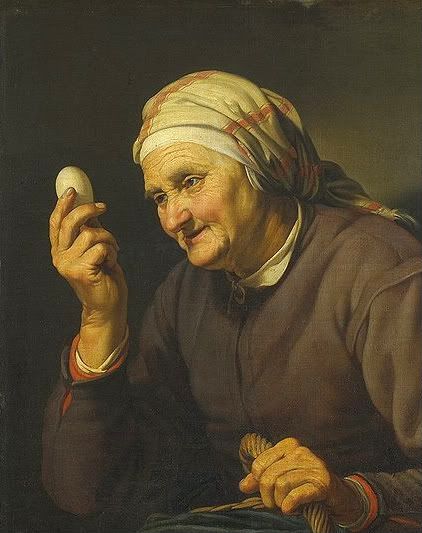

As she was thinking this, and wondering how she would live, Lillian spied on the shelf where she had placed the urn a perfectly ovoid stone she had given to her son as a toy when he was small. It was the size of an ordinary hen’s egg, and splattered with star-shaped markings that seemed to be made of inlaid ivory but were in fact traces of the ancient combustion that had brought the stone into its first, rough being. The sight of it filled her with joy because it had been his. It did not matter that it had been a gift from her to him, or that her son had not cared enough for it to take it with him in his travels. She was certain that the egg held the power to transport her into his presence, and she swore to herself to keep it by her always.

That night, holding the egg in her hand, she dreamed of a city he had often traveled to and described to her in his letters. She stood at the head of a market street which was famous for housing merchants from every corner of the world, and where it was possible, he had written her, to find every ingredient for every dish ever consumed by man or woman. As she stood there wondering what she might buy, she saw her son standing a little ways off, glancing sidelong at her. She reached out her hand, which he took, and together they wandered down the street, pondering the various shop names, which were written in innumerable, inscrutable languages. The next morning, when Lillian awoke, she carefully placed the egg in the pocket of her skirt, so that all day long she felt the comforting tug of its weight at her side, and that night and for many nights afterwards she flew on its stone back to meet her son in some distant place. He was always waiting there for her, with his gentle, furtive smile. Always he took her hand and they walked together down busy streets or through plazas made of wood or stone or alongside dark canals splashed with sunlight.

One night, Lillian met her son on a street corner of the city where he had died, and as she reached out to take his hand she felt the stone egg slip from her grasp into his. At this perceptible lightening she realized, for the first time, that she had rashly brought the egg into the dream with her, and she felt a bottomless dread over its loss, as we sometimes do in dreams when an object of mysterious value has been misplaced. He showed her the egg, resting safe on his upturned palm, and placing it in the pocket of his coat he guided her down the street, as gentle as ever, but in the morning when Lillian awoke the egg was gone. She tore apart the bed covers, she looked under the bed, thinking it might have rolled under there while she slept, but the egg was not to be found.

After that, the dream encounters ceased. The letters Lillian had so carefully preserved lay quietly in their box, turning into dust, next to the brass urn, and the long future she had imagined for herself began to unfold.

Michele Stepto says: I have taught in the English and African-American Studies departments at Yale and at the Bread Loaf School of English in Vermont, and have published a translation from the Spanish of the Catalina Erauso memoir under the title, Lieutenant Nun: Memoir of a Basque Transvestite in the New World, along with works of history and fiction for younger readers. An earlier short story, "Pagoda," appeared in the magazine Italian-Americana.

What do you think is the most important part of a fantasy story?

I think that fantasy is allied to the wish, and that fantasy stories express deep wishes: that the one we love might love us, that we might punish those who have hurt us, that we might free ourselves from our oppressors or escape intolerable circumstances, that we might bring back from the dead the ones we love. Sometimes in dreams such wishes come true, and for this reason fantasy and the dream are closely related. But they rarely come true in waking life, in real life, though we go on wishing anyway. Fantasy exists to answer such wishing.

0 comments:

Post a Comment