The

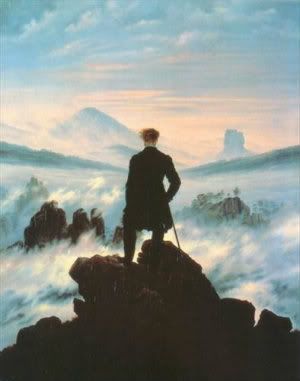

Fog Lake

by Anahita Ayasoufi

The

first time I encountered the fog lake, I was nine, sitting on the back seat of

Daddy’s 1991 VW, breathing through the dirt the car raised as it revved around

the mountain, fearing every minute that it would slip one too many pebbles,

sending us head first in the valley. That’s why I kept an eye on the valley,

and that’s how I saw the fog lake. I took it as a real lake, steaming white,

but still a lake one could boat or swim in. It was the way its edges blended in

clouds that made me ask, “Daddy, what lake is that?”

“It’s

not a lake, Laurence; it’s fog.”

Fog—dense

flowing fog.

“Does

it ever clear?” I asked.

“Not

that I’ve heard of,” he said. And Daddy grew up in the village just below the

fog line, midway between the summit forest and the dirt road slipping all the

way down to the ocean. If he never heard of it, it had never happened.

“What’s

under the fog?” I asked.

“Extension

of the valley, perhaps—it’s rather remote.” Daddy said.

It

did seem out of reach, way too steep to stir local explorers’ interest.

“But,

how do you know it’s the extension of the valley, if the fog has never

cleared?” I asked.

Daddy

glanced at me in the mirror, the same look I saw on his face when he told me

bedtime stories.

“It

may be a lake. No one knows. Some say it’s a portal to another realm; some say

angels fly there; some say hideous creatures lurk there.” Daddy made claws and

roared, as he did when he wanted to make me laugh.

I

knew from that moment that I would go back to the fog lake. Daddy never gave in

to taking me there. It was way too dangerous for a boy. But it became my

obsession. I prepared for it every day of my life. I read about camping. I

practiced surviving in the wilderness of my backyard. I practiced mountain

climbing every dawn at the rocky hills that bordered our town. I worked out

every evening. I took swimming classes at school and aced them, in case the fog

lake was really a lake. If it was, I would name it Lake Laurence.

One

weekend morning, when I was sixteen, I sneaked in Daddy’s car and drove to my

dream. The dirt road curled as I remembered, and the old VW was still agile

enough to make the turns. At the summit, where the road started to slip back

down, I took a side track hoping the car would make it on the falling leaves,

hoping to get a closer view of the fog lake. When it defied precaution to move

forward, I stepped out of the car and stood at the edge. I gauged the slope. I

listened to the wind. I tested the rocks for stability. I tested the strength

of the trees for holding my rope. I wanted to know exactly what I was facing,

and it was harder than I had thought—the pebbles were slippery, the trees

feeble, and the faint howling in horizon hinted at the possibility of wild

animals down there. I was not prepared yet, but I would come back someday soon

when I was.

I

took skydiving to overcome my shyness of the heights. I took an after school

job at the zoo, feeding the wild, learning their ways, facing my fears. I wanted

to be prepared for anything, absolutely anything. Meanwhile, swimming remained

my strength. My records always appeared on top of the lists, until one day someone

beat them—her name was Lily.

I

met Lily the last year of high school. She moved in our town from a mountain

range. I saw her first in bathing suit, sitting by the edge of the community

pool, her legs making gentle whirlpools in water.

I

marveled how she had won the record. Lily was tall, granted, but not taller

than I was. And she didn’t have the muscles that I had worked on for so long.

Her skin seemed so transparent one would think she’d never seen the sun. Her

reddish hair only made the paleness of her skin more apparent. Yet, she did win

that record, and every other one.

I

asked her how.

“Swimming

is like flying, only in water,” she said. “I like your focus.”

My

focus became her focus for the next three months. She dug in deep, until she

reached the fog lake. She made me ramble about it many times. Her smile

encouraged me, making my head spin, as if I was drunk. I still wanted to know

how she had won. Her answer always revolved around flying. I started dreaming

of her flying in the sky.

Lily

didn’t talk much with other boys, or girls for that matter. As the time went

on, I felt a heat building up between us. I started to yearn for seeing her.

Her image became more and more colorful in my dreams. Before long, her thought

had strengthened enough to overpower any other thought, including the fog lake.

Deep down, I felt happy to let the new obsession replace the old obsession.

Someday, when prepared, I would ask her to be my girlfriend, someday soon.

I

was preparing for that day, watching her interests, learning about what girls

wanted, and I know I would have succeeded, had she not kept harping on the fog

lake. Somehow I had missed the point where the lake became her obsession

instead of mine.

Both

our obsessions built up to their heights. It was an early Sunday morning—one of

the Sundays that she accompanied me to the rocky hills—that I realized she had

packed a far larger backpack than needed.

She

spread a map on the ground.

“I

have marked the dirt paths. If we take the hilltop, we’ll reach the fog lake in

two hours. It’s a shortcut. We won’t need a car.”

I

watched her for a moment—serious, serious madness.

“We’ll

need to plan this, Lily. We’ll need to rent a Jeep, hire a guide—”

“You

don’t have to come,” she said, in the kindest tone I had heard.

“I

damn will,” I heard myself saying. And I felt the thrill, not so much the

thrill of touching my lake, but the thrill of having Lily where no eyes could

see us. And I feared it, because I had dreamt of it for too long. I didn’t feel

prepared.

Lily

was already hiking. All I had to do was follow. I did.

After

half an hour of creaking over pebbles, the morning sun in our face, we reached

the edge of the forest. Tall maple trees in early fall colors sieved the

sunlight. In the forest, the sound of us crunching the leaves mixed with the

birds’ singing made it hard for me to hear her breaths. I have been listening

to her breathing for the past half-hour, forgetting that I had to text Daddy to

tell him not to wait for me for lunch. He wouldn’t mind.

“Are

your parents OK with this trip?” I asked.

Lily’s

gaze searched my eyes as if that was something I should have known better than

to ask. I tried to remember what I had missed. All that came to my mind was her

remarks about flying. I had never heard her talk of her parents.

After

another hour of hiking, my excuse-touching her arms every now and then, her

immersing in her map, I felt butterflies in my stomach. The wind felt stronger,

the chill more penetrating, the forest darker.

“It

feels like late afternoon, and it’s hardly even noon,” I said.

“We’re

half an hour from the summit. From there, another half an hour of descent, and

your fog lake should be in reach.” I never thought in my life, I would meet

someone more devoted to exploring that lake than I was. Yet, the wind howling

among the trees had started to feel unpleasant.

“What

if we returned and came back more prepared?” We had walked on no path for a

while. This was the territory of the untouched, too close to the fog to

explore.

“What

if there’s nothing interesting in there? What if we get in and get lost?” I

asked.

“Do

you believe in guardian angels?”Lilly said.

I

was too cold at that point to warm up to her smile. Only then I realized she

had never put on a coat. The bare arms I have been touching all along, felt as

warm as a summer noon. I sensed a faint glow in her gaze, a glow I had somehow

missed before.

When

we stood at the summit, before crossing the last row of maple trees to where we

should see the fog, the howling of the wind strengthened. The sky felt as dark

as dusk, and I knew the howling wasn’t of the wind anymore—the throats

generating it had gleaming eyes attached, red eyes—wolves.

I

never screamed, not when I saw the wolves, not when I saw Lily squat down and

speak with them, not when she turned and her eyes glowed brighter than the eyes

of those creatures, not when the wolves passed me by, growling, their fur

almost touching my chest. I had frozen still, thinking of the hideous creatures

that could live in here, thinking Lily could be one of them.

“It’s

a few more steps,” Lily said, her eyes back to normal.

The

fog lake was beneath my feet, about half a mile down the steepest slope. Lilly

touched my hand. “Here’s your dream.”

There

were my dreams, both of them, my mysterious girl and my mysterious lake. And

they both felt out of reach. Dizziness settled in as I watched the slope. A

moderately strong wind could make us lose balance. We had no ropes, no guides,

no anchors.

Lily

watched me, her eyes expecting. Then her gaze pointed down, her long lashes

hiding its glow.

“I

think we should return,” I said, trying to pull her back, backing off

myself.

She detached her hand of mine.

“Laurence,

here we part,” Lilly said. She opened her arms. The darkness cleared, as if her

palms had pushed it aside. I shielded my eyes from the brightness that was

blinding me. I curled up in pain. When I could see again, Lily’s white feathers

were shielding the wind. It felt as if she had covered the entire sky.

She

flew by me, soared and blended in the fog. I lost balance in the wake of her

wings.

All

I remember is the weightless drop, and the press of the forces I knew I had

evoked by obsessing and preparing, the forces that I had enraged by backing

off.

Daddy

says they found me unconscious by the seashore, miles away from the Fog Lake.

He says I was curled up, bare and clutching a three-foot feather in my arms.

I

have kept her feather. I know I will return to the Fog Lake someday far in the

future to take that leap, to join my angel, but the time has to be ripe. It has

to be when I’m equipped, when I know the way, when I’m ready, when I’m….

* * *

Anahita Ayasoufi teaches at East Tennessee State University. Her fiction has appeared (or

is scheduled to appear) in Bosley Gravel's Cavalcade of Terror, Yesteryear

Fiction, Liquid Imagination, and Lorelei Signal.

Where do you get the ideas for your stories?I usually start describing something that has impacted me in someway. Sometimes it turns to a story right away; sometimes it sits there for a while before connecting with another idea and becoming a story.

What inspires you to write and keep writing?The desire to stir the emotion of my audience, to cause pleasure in someway, somehow. I don't know if I'm successful in achieving that, but it's the goal.

What do you think is the most important part of a fantasy story? For me, the fact that it's different from the world I'm used and see everyday.

What do you think is the attraction of the fantasy genre? The feeling and touching of the surreal.

What advice do you have for other fantasy writers? I don't quite see myself in a place of giving advice. But if I must say something, it'll be this: I love fantasy. Please keep writing it.

0 comments:

Post a Comment