Woman of the Small Magic

by Diane Gallant

Jemu was thinking of her when she appeared, so that it seemed to be his thought which summoned her. He remembered how she had moved lightly among the dancers in the hall, and taken her place on the red cushion beside Lor’s chair. A daughter perhaps, or a favorite concubine. And Jemu remembered the laughter that had glittered in her dark eyes as she watched his charlatan’s magic -- the fire that erupted from the end of his cane, the shrinking cat, the ruby ring that floated in the air -- illusions and tricks which he’d learned in the east, and which had served him well for a long time, giving him a traveling entertainer’s entrance into the noble houses of the great cities of Prog. Once inside the houses, the real trick was to find gold and jewelry and valuable items, and to carry them out, undetected.

Last night, Jemu had failed.

And now he was here, under Lor’s house, in a prison cell not quite big enough for a man to lie down in, sitting on the dirt floor with his back against the cold, humid stone of the wall. Rusty iron bars locked him in this small space, and five drooling, snarling dogs kept guard outside the bars. He expected that Lor’s men would come in the full light of morning, and bind his hands behind his back, and lead him out into the garden, and hang him there, among the green trees and babbling blue fountains. And while waiting for the brutes to come and bring him to his death, he was thinking of the girl with the laughing eyes who sat at Lor’s feet.

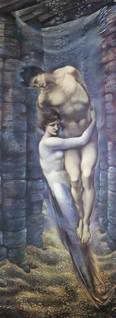

Instead, it was the girl who came. He heard her before he saw her. She was in the corridor above him, or perhaps at the top of the stone stairs that led down to his cell, and she was speaking words that Jemu did not understand -- a foreign language, or a spell. She was speaking quickly. Her voice was low, barely more that a whisper, and it rolled like tidewater over the heads of the drooling dogs, and through the iron bars and into Jemu’s cell, and as it went it spread an eerie calm. The dogs reacted immediately. They whimpered first, then quieted completely, and finally lay down in the dirt with their eyes closed.

Then the girl -- no, thought Jemu, the woman -- appeared in the doorway at the bottom of the stairs. She took a rapid survey of the scene, and stopped her incantation. There was no laughter in her eyes now, only a grim determination. She wore black riding boots, and a dark green riding cloak with the hood pushed back, and her black hair was bound tightly behind her head. She pulled the key from the hook where it hung on the far wall, and without hesitation she stepped over the heads of the sleeping dogs and came to the door of Jemu’s cell. She tuned the key in the lock, and pulled the door, which screeched on its hinges as it opened. She threw the key to the floor, and held out her hand to Jemu. “Come,” she said in his own language. “Come quickly.”

“Who are you?” he asked. “What are you doing here?”

“I’m saving your life. Come.”

“Why?”

“No time to discuss it now. Come.”

Jemu’s legs shook beneath him as he stood. “Where are we going?”

The woman grabbed him by the arm, and tugged him, hard. “Follow me. Come.”

He followed her up the stairs and through a winding passageway into a wide corridor which led, he thought, to the great hall where he had given his performance the night before. She turned instead into a narrow side corridor, and led Jemu down some low steps to a small door of heavy masonry, which she pushed open with some effort. They stepped through this door, and it closed behind them. Jemu saw that from the outside the door was invisible against the brick wall of Lor’s foundation. They had come through a little-known -- hence unguarded -- exit, and they were now outside, standing under a sky that was already beginning to glow in the east.

“Day is coming,” said the woman. “Hurry. Follow me.”

They walked quickly, but they did not run -- that would have aroused suspicion. And they did not look continually from side to side, and behind them, like pursued criminals. Instead, they were careful to keep their eyes focused on the road before them.

Near the outer limit of the city, they came to a complex of low, wooden buildings -- stables by the smell -- and the woman pulled Jemu through the open door of one of these buildings. Inside, an old man worked alone, brushing a horse. He came forward when he saw the woman.

“Ralla,” he said, smiling toothlessly. “So nice.”

“Gordo, I need horses. Two of them.”

Here Jemu, who had been quiet since leaving his prison, finally spoke. “Two horses?”

The woman named Ralla spoke to Jemu without looking at him. “Two horses. I’m going with you. He’ll find his dogs asleep, and he’ll know it was me. He’ll kill me.”

The old man leaned forward on the balls of his feet. He peered up at Jemu, and then looked back at Ralla. “You have trouble? What is wrong?”

“Gordo, you’ve been a friend for a long time. Please don’t ask me questions.”

The man nodded, and stepped back on his heels. “I know two horses I can lend you. Their master won’t miss ‘em for a while. But you send ‘em back, yeah?”

“Have I ever let you down?”

The man pointed to two geldings, one brown, the other spotted. “Those over there. I’ll get ‘em saddled up for you.”

“You’re wonderful.”

The man wagged his finger at her. “You just be sure you send ‘em back right away.”

Ralla kissed them man’s cheek, and he blushed.

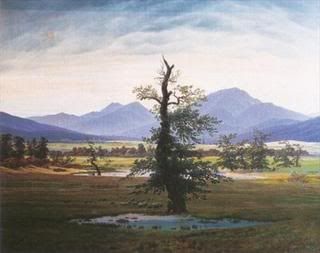

And that is how, on the morning of his execution, with the rising sun casting tall shadows before him, Jemu found himself riding away from the city on a fast horse, beside a strange, dark-eyed woman who knew how to charm dogs to sleep.

* * *They rode westward all morning, passing through wild lands dotted with occasional farms and villages, and encountering very few other travelers on their way. It was midday when Jemu noticed that the road was wider, better maintained, busier -- all signs that they were approaching the next city. Ralla led the way to the stables of a large farm, where she left the horses in the care of a young boy. She threw him a coin, saying, “Jakko, return these horses to your uncle Gordo for me, will you?” The boy caught the coin out of the air, and kissed it. Then Ralla led Jemu into the city on foot.

“I appreciate what you’ve done,” Jemu told her as they walked.

She glanced sidelong at him as they walked. “Don’t thank me -- you’re not free yet. They’re going to hunt you down. Both of us.”

“Well, I

am thanking you. I was in a big mess back there.” He looked at her again, and saw the focused intent in her eyes, the frown that now replaced the smile of the night before. “What about you? What are you running from?”

She laughed sarcastically. “What am I running from? Let’s see, there are so many things -- barbarism, slavery, evil politics, a forced marriage…”

“You were getting married?”

“Within these three weeks, that’s right. Let’s see, where was I? -- a forced marriage, imprisonment, the complete loss of my power to a husband of Lor’s choosing…”

“So your father was forcing you to marry against your will?”

“Lor is my uncle, and yes, he was.”

“And your husband-to-be was…”

“

Is an evil man. And he will be looking for me.”

“So why stop to save me? Why not just save yourself?”

Ralla hesitated, then said, “I don’t know why, really, other than just being sick of my uncle and his cruelty. I saw your performance yesterday in the hall, and you seem to me a trickster and a petty, common thief. My uncle should have had you whipped, and stripped of your possessions, and then he should have let you go.”

Jemu raised his eyebrows at this. “Really?”

“It’s what you deserve. It’s what I would have done.”

“But you wouldn’t hang me.”

She shook her head. “That would be excessive, and more than you deserve.”

They walked on in silence for some time, and as they walked, a city sprang up around them, noisy and bustling. There were buildings three and four stories high rising up at the sides of the streets, their sagging balconies hanging precariously over the heads of passersby. Signs hanging over doors announced shoemakers and tailors and jewelers. Children ran with hoops and balls, merchants pulled donkeys, and women carried baskets on their shoulders.

Ralla stopped near the gate of a large open-air market. She stared at the ground for some seconds, and pursed her lips. Jemu opened his mouth to speak, but Ralla interrupted him. “If we stay in the city and try to hide in the crowd, we’ll be caught by the end of the week, I am certain of it. If we take to the road, we’ll be caught by nightfall. Either way we’re fools. I’ve been thinking about this all day.”

“There’s no hope, then,” said Jemu. “Maybe if we go our separate ways.”

She looked at him harshly, then shrugged. “Go your own way if you wish. But you should know this -- Lor has his fingers everywhere in Prog. Alone or together, the only hope for either of us is to leave Prog altogether. This is what I have been thinking all day.”

“Leave Prog?”

Ralla nodded. “We have to go north, to Sumtur. The king there does not tolerate corruption and shady politicking, which is how Lor operates. We’ll be safe there, and you can go your own way. You can change your name, make yourself a new life.”

Jemu laughed and waved his hand dismissively. “Sumtur is no place for a traveling entertainer.”

“It’s no place for a traveling thief, you’re right. Maybe you’ll find a more honest line of work.” Jemu heard the scorn in Ralla’s voice as she said this.

Jemu shook his head. “I think I’ll pass.”

She spun to face him. “So you’ll stay in Prog then, and you’ll be caught, and under torture you’ll tell them about my role in your escape and about my going to Sumtur. And you’ll beg for your life like a dog, but you’ll be killed anyway, and my friend Gordo and his young nephew will be killed right along with you. And that is how you plan to pay me back for saving your life?”

Jemu felt the shame rise, stinging and red-hot, to his cheeks. “So we go to Sumtur, then?”

Ralla smiled the tiniest smile. “And by the quickest, most direct way,” she said.

At the market, Jemu and Ralla bought preserved foods, tools, fishing gear, a small dry tent, weapons, blankets, canteens, a fire-starting kit -- in short, everything two travelers would need for a ten-day trek, on foot, through the wild -- for, as Ralla explained, the quickest, most direct way to Sumtur was through the mountains to the north. Jemu pointed out that the mountains were wild and unmapped, and that great, ferocious beasts roamed freely there -- or so he had heard. But Ralla said that this was not a problem, as they were less likely to be pursued in wild places. Besides, she told him, she had a certain way with beasts. Jemu knew this to be true, but he felt overwhelmed by her already, and did not want to ask her any questions about this just yet.

* * * All that afternoon, Jemu and Ralla followed the trail that led from the grassy plain outside the city’s boundaries to the mountains in the north, and by nightfall they were already high in foothills, where they made their camp. They sat in the light of their campfire, Jemu selecting small stones and twigs and making them levitate, or disappear altogether, and Ralla laughing for the first time that day. And it was only then that Jemu found the courage to ask her, “What did you do to the dogs?”

“I put them to sleep,” said Ralla. “I didn’t hurt them.”

“How did you do it?”

“I spoke to them in a certain way. I commanded them to sleep.”

“But how did you know how to speak to them?”

Ralla shrugged. “I was born knowing. It’s a small magic, really, and it’s the only trick I know.”

“Can you make anything fall asleep?”

“Anything not human I can. Any animal.”

“Do they wake up?”

“Of course,” she said. “After a day or two, they wake up hungry and grouchy. Like I said before, it’s only a small magic.”

“But it’s

real magic.”

Ralla nodded. “Yes. But I am not the only one with real magic. This is another thing you should understand, Jemu. The man I was to marry, he possesses a greater magic than mine.”

Jemu’s voice dropped to a whisper. “A wizard?”

Ralla nodded again. “This man, this wizard, he receives the perceptions of beasts telepathically -- land animals, you understand, not birds or fish -- and whatever things these animals taste and smell and hear and see and feel, this man also perceives from a distance. This makes him dangerous to us. He is also a shapeshifter.”

“A shapeshifter,” Jemus repeated, still speaking in a whisper.

“He can temporarily assume the shape of any animal that does not swim or fly.”

“He cannot fly?” asked Jemu. This thought gave him some small comfort, and he wanted to hear Ralla repeat it.

“No. There are wizards who can assume the form of birds, but they are his mortal enemies. The man I was to marry can take the shape of any beast that runs or crawls on land. But it’s difficult magic, and in animal form he tires and weakens quickly. But still, you see, he is a dangerous enemy.”

“And you think he will come for us?”

“He will look for us through the senses of animals. As for

coming behind us, I think he might try.”

“Then why did you bring us here, where there are so many beasts to see us?”

Ralla shook her head. “Jemu, he is as likely to see us through the eyes of a city rat or a chicken in a wire cage as he likely to see us through the eyes of a bear or a mountain lion. And here, at least, we… I… can charm the animals that come near us.”

Jemu perked up, giddy for a second with the new realization. “And he can’t receive information through the senses of sleeping animals.”

“That’s correct, he can’t.”

Ralla asked Jemu to do more of his magician’s tricks, but Jemu’s heart wasn’t there, and he dropped the floating twigs, and the disappearing stones would not disappear, and Ralla laughed even harder than before. At last she began to yawn, and said they should probably try to sleep.

Then Ralla sang a song, low and sweet, in a foreign language which for all his travels Jemu could not identify. Ralla said her song was a night song whose magic would linger in the air until dawn. She slept peacefully then, but Jemu sat awake for a long time, listening for the sound of animals in the trees.

* * *The next few days of their trek through the mountains were warm and humid. Ralla had shed her riding cloak by now, and instead she wore soft brown trousers and a white top that left her arms and shoulders bare. She carried her share of their provisions on her back, and Jemu saw that she stooped under the weight. He offered to shoulder her pack for a little while, but she refused.

The ground beneath them climbed steeply now, and Jemu and Ralla found they needed to stop and rest frequently. During one of these rest-stops, Ralla said that she thought they would be wise to move at a faster pace. She said that she detected something strange, a kind of watchful malevolence, in the animals that crossed her path. Hearing this, Jemu felt uneasy again.

Ralla laid her hand on his arm, gently. “We’ll do what we can do,” she said, “and we won’t worry about the rest. And soon you’ll be in the Sumtur capital, with your new name and your new identity and your old bag of tricks, performing for the king.”

Later, Jemu lay under the branches of a tall pine, with his arms folded behind his head, and there he fell into a fretful, shallow sleep. He woke to the twin sounds of water splashing and Ralla’s strange spell-casting. He stood, and followed the sounds to a shady stream where Ralla was bathing, and he watched her from the trees. With her dark hair unbound and falling over her shoulders, she looked more like the girl Jemu first saw seated on the cushion at the foot of Lor’s chair. He watched her body as she emerged from the water. She was very beautiful, but something was not quite right with the picture. She was too pale, and very listless. She stood for some seconds, limp as a rag doll, with her shoulders stooped and her head bent forward. Then she did a strange thing -- she lay down in the cool dark mud of the stream’s bank.

Jemu approached cautiously, and knelt in the mud beside her. He leaned over her and listened for the sound of breathing. “Ralla,” he said.

She opened her eyes at once and looked at him blankly. It was several seconds, he thought, before recognition dawned in her eyes. Then she sat up suddenly and covered herself with one arm as she reached for her clothes with the other.

“Are you feeling alright? Are you ill?”

“I’m fine,” she said. “Just a little warm is all.”

Jemu diverted his eyes while she fumbled for her clothes. She dressed quickly, oblivious to the water and mud which still clung to her skin. Then she jumped to her feet. “Let’s go,” she said.

“Are you sure you’re well?” Jemu asked.

“I’m fine.”

“Let me carry your pack.”

She shook her head fiercely. “No.”

They continued walking, following the trail higher into the mountains. But Ralla wasn’t fine, and soon they had to stop again. Her eyes were glossy, and her face was flushed. “I have to rest a while,” she said. “In a safe place.”

Jemu and Ralla found a cool, shallow cave concealed among the mountain’s many places of rock, and Ralla sang the sleeping song to any animals that might have lived within, while Jemu used the canvas of the tent to camouflage the crevice that was the entrance to the cave. Ralla lay on the floor, and Jemu put his hand to her forehead. “You have a fever,” he said.

Ralla clasped Jemu’s hand. “I know… I know a remedy for this,” she whispered. “You must go and find something for me. Dangar leaves, you know them? They look like… like weeds.”

Jemu nodded. “The prickly leaves, the dark ones. They grow in the brush.”

“Yes. You bring some here, and boil them, and I drink. Then we go… we go to Sumtur.”

“These leaves will make you well? Is this more magic?”

Ralla shook her head. “Not magic, just medicine. Bring them quick. We can’t… can’t waste time.”

Jemu nodded and turned to go, but Ralla grabbed his arm. “Don’t go far,” she said. “And avoid animals.”

Outside the concealed entrance of the cave, Jemu looked around. The land here was rocky and barren, and the few, sparse plants that grew here were not the plants he needed. Jemu had to walk some distance before finding a place trees grew and where the underbrush was thick, a place where he might find what he needed.

Off on his own, Jemu was especially aware of the sounds around him. He heard the rustling of small animals in the leaves around his feet, and in the branches of the trees above him. Ralla had told him to avoid animals, but he did not know how this would be possible. The trick was, he thought, to find the dangar leaves as quickly as possible, to bring the medicine to Ralla as soon as possible, and to get out of these cursed mountains and into Sumtur as fast as possible. There he would be free of this witch woman who, though beautiful, was only a woman of small magic, and really more trouble than she was worth.

As he rummaged through patches of weeds, scratching his arms and cutting his hands and cursing softly, Jemu became aware of another sound. It was a scraping and rustling sound, loud, heavy and ominous. Jemu looked up and saw, not far from the place where he crouched in the brush, a large black bear standing on its back legs and sniffing the air. Jemu put one hand on the ground and the other on the trunk of a tree, for balance, and he held his breath.

A good try, but unsuccessful. The bear saw him, and walking upright like a man, the bear approached. When the bear stood not ten paces from Jemu, he moved his head and stretched his back and haunches, and the contours of his body shifted, slightly at first, then more critically, until the bear appeared to be not a bear at all but…

Jemu gasped. Before him stood a great, hulking shape of a man, and Jemu knew it must be Ralla’s wizard. His hair was long and wild and gray, and his skin was brown and deeply creased like the trunk of a tree, and his eyes were filled with dark fire, and when he spoke his voice was like the roar of a lion. “Where is she?”

“Where is who?” said Jemu.

“The girl. Where is she?”

“Girl?”

“Don’t play dumb with me, little man. Where is the girl?”

Jemu stood up. “I don’t know. She left days ago, said something about going west, to Navron, I think it was.”

“I should kill you for lying.”

Jemu feigned brave indifference. He shrugged. “I don’t know where she is.”

“Listen. I could kill you right now. And I will, if you don’t lead me to her.”

Jemu hesitated before answering. “I… can’t help you.”

The wizard reached out his hand, which Jemu saw was now furred and clawed like the paw of a bear, and put it on Jemu’s neck, and began to squeeze. “Tell. Me. Where. She. Is.” Then he pushed Jemu away, letting him fall back into the brush, and said, “If you tell me now, I will let you go, free and unharmed. If you do not tell me now, I will kill you, and

then I will find her anyway. Do not think that you can protect her.”

Jemu rose, stumbling, to his feet, his hands holding his neck. “You’ll let me go? You won’t hurt me?” he asked. His voice was hoarse and ragged.

The wizard put his hand -- now a human hand again, with long crooked fingers and long yellow nails -- on his heart. “I give my word as a wizard. But you must tell me now.”

“She is hiding from you.”

“Yes,

fool, this much I know.”

Jemu took removed one hand from his neck, and pointed. “In a cave.”

“Where?” said the wizard. “Bring me to her.”

* * * Jemu pushed aside the canvas cover of the cave opening, and peeked inside. Ralla sat up, and looked at Jemu with burning eyes. She spoke quickly and feverishly. “Jemu, I figured it out. He knows I’m up here, and he’s the one making me sick. He’s reaching out through the senses of the animals, and he detects a blank streak along the path we’ve followed. But he can’t pinpoint me precisely. And he must not. Here’s what we can do…”

Before she could say anymore, the wizard stepped forward and stood behind Jemu’s shoulder. “It’s too late, my dear,” he said.

Ralla looked from Jemu to the wizard, and back to Jemu. She wore a look of bewildered outrage on her face. “You betrayed me,” she told Jemu.

The wizard pushed Jemu out of the way, and entered the cave. “Now, Ralla, you must not be too hard on him,” he said, waving a long fingered hand dismissively. “He is only a small man, and his thoughts are small. He thinks of no more than getting away from here, free and unharmed -- that’s free of you, my dear, free to perform his charlatan’s tricks in the noble houses of Sumtur.”

Ralla stared at Jemu, and Jemu felt that she could flay him alive with that stare. The wizard put a long fingered hand under Ralla’s chin, and picked up her face so that she was looking at

him. “I will return you to your home, and you will recover. We will be married as planned, and you will yield your power to me.”

She pulled her head from the wizard’s grip, and spit on his hand. The wizard wrinkled his nose slightly in disgust, and then took out a handkerchief and wiped his hand. “Very well, my dear,” he said to Ralla. “We’ll do it the easy way, or we’ll do it the hard way.” Then he raised his hand, and brought it down, hard, on the side of Ralla’s face. She shrank back, and began to sob.

Then he turned to Jemu, and there was contempt in his voice when he spoke. “You may go now, free and unharmed, as agreed.” He waved his hand again, dismissing Jemu. “Go and live your small man’s life.”

Jemu looked at Ralla, but her face was hidden, buried in her hands. He picked up his pack and threw it over his shoulder. Then he pulled open the canvas which covered the opening of the cave, looked back once more at Ralla, then turned away and stepped outside.

* * * Jemu left Ralla with the wizard, and walked the trail alone.

The next day, the trail began its gradual descent into Sumtur. Now Jemu knew without a doubt that he was going to survive, that he would arrive safely in a land that was beyond the reach of his enemies, where he would perform his “magic” again. But he could not remember any time in his life when he felt more worthless or more ashamed. That is why, before the sun had reached its zenith, Jemu had turned around, and was heading south, back over the mountains, towards Prog.

Jemu moved quickly now, with purpose and decisiveness, and by nightfall he reached the small cave where he left Ralla. He was not surprised to find it vacated. He camped there, and in the morning he continued moving south.

He caught up with them late in the day, as he passed back over parts of the trail he remembered traveling with Ralla. Jemu heard the wizard’s voice while he was still some distance away. The wizard was admonishing Ralla for her stubbornness and her willfulness, telling her that soon her will would learn to bend, soon she would learn sacrifice and selfless contentment. Jemu was careful to remain concealed and quiet as he followed the voice.

He saw them, then, and he hid in the trees and he watched. Ralla sat on the ground, gagged and with her hands bound. From the lethargic way she held herself, it was obvious that the wizard had not removed the illness from her. The wizard commanded her to stand and walk on the trail, but she did not. He commanded her again, and still she did not. The wizard muttered some curses, then began to laugh softly. He wagged his finger at her and said, “Good. Very good you are. You can disable my magic like no animal can. I

approve. I

enjoy the fact that you are still strong, still

magically strong in spite of your illness. I am

pleased by this, because soon the power your possess will be added to mine, like a tributary flowing into a great river.” He laughed some more, and said, “So fight your best fight, my lovely bride. Show me all your power. I will carry you down this mountain the non-magical way, I will drag you by your hair if I must, and then we will settle matters.” Then he walked away from her, still laughing, and began setting up the tent.

Very quietly in the failing light of day, Jemu came out of hiding. Crouching, he approached Ralla, and pulled the gag out of her mouth. “I’m going to save you,” he whispered, “as you saved me.”

There was no emotion visible in Ralla’s face -- no surprise or fear or happiness or anger. There was only the fever shining in her eyes. Her voice was low and strained. “Make him shift. Animals are weak to me.”

“Shapeshift? How?”

Ralla shook her head slowly. “He won’t. He’s too smart. Only if his enemies come.”

“If his enemies come?”

“Bring the bird wizards. He will shift to fight them.”

Bird wizards? thought Jemu. “Ralla, you’re very ill. The fever is…”

“Listen,” she said. “Use your magic.”

“But I don’t have magic.”

The wizard, meanwhile, had finished setting up camp. He stood with his back to Ralla, surveying the tent which stood sagging and leaning under the rapidly darkening sky. “Go now,” Ralla told Jemu. “Put my gag back. Put it loose.”

Jemu did as she asked, putting the gag in so that she could spit it out when she wanted. Then he hid himself in the shadows among the trees, and thought. Ralla had once told him that the wizard could assume the shapes of animals that moved on land only, and that those other wizards who took the shapes of birds were his mortal enemies. If he wanted the wizard to shift into animal shape, he needed to bring those enemies now.

But how, he wondered.

Use your magic, Ralla had said. Jemu thought about this. He didn’t have any real magic, he had only tricks and illusions. And then, all at once, he knew the answer.

* * * The wizard was a wizard, fearsome and powerful, but at night he slept like other men. And on this night he slept in a small, sagging tent on the side of a mountain, vulnerable to his enemies.

In the moonlight outside the tent, Jemu worked his magic, as he did so many times before. And like so many times before, he did it not for its own sake, but with a ulterior purpose in his heart.

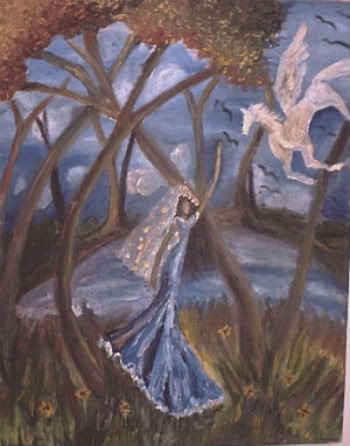

First there were sounds -- the deep-throated cawing of birds, and the flutter of great wings. Jemu watched the small tent for signs that someone inside -- someone large -- was stirring in his sleep, and waking up. Then came the visual illusions, played out against the moonlit canvas of the tent. There were the shadows of great, terrifying birds, whose shapes dissolved into the large, hulking shapes of men. The man-shapes bent their heads together, and whispered evil counsel among themselves, and then melted back into the horrid shapes of birds. Then the bird-shapes moved their heads and beaks and claws, and their shadows grew larger and more terrible as they approached the opening of the tent.

Jemu heard sounds of rustling and scraping inside the tent. He bent his head and listened, holding his breath. There was a loud growl and a ripping noise as the tent was torn open

from the inside, and a large black bear walked out into the moonlight on his hind legs. Jemu’s magic had worked. The wizard had come to fight his enemies.

Later, and forever after, Jemu would doubt that the wizard realized his mistake that night. The singing of the strange incantation began before the bear had time to locate his enemies among the shadows. Ralla’s voice was still weak, still strained, but her song flooded the quiet night with magic. The bear dropped heavily to his knees, and fell forward, exactly as a man would fall.

When the song ended, Jemu went to Ralla and pulled her hands free from their bonds, and helped her to her feet. Her face was sweaty and dirty, and her eyes were rimmed with dark circles. But already she was cool to the touch, and her spirits were higher than they had been in many days. “Come and see,” she said, taking Jemu’s hand.

Ralla stooped over the body of the sleeping bear, and examined him closely. Then she began to walk in circles around him, chanting a new spell, and as she did so, the form of the sleeping bear dissolved into that of a sleeping man. Jemu was frightened, and stepped back.

“All is well,” said Ralla. “He is harmless. He will wake in a day or two, and he will be hungry and very angry.”

“And he’ll hunt in these mountains until he finds us. We should kill him.”

Ralla shook her head. “I don’t think so, Jemu. I have taken his powers, as he meant to take mine. He is a man without magic now. He will not find us.”

“You have taken his powers? Then you are…”

“A shapeshifter, yes,” Ralla said. “And I can perceive the world through the senses of animals. But I can’t fly or swim, I think. And I still have my own small magic. I still know the sleeping charm.”

“And will you still go to Sumtur?”

Ralla glanced down at the sleeping wizard, and shivered. “I will go without delay,” she said. “I will go into Sumtur like a storm.” And with that she blurred around the edges, and her form shifted, and she became a strong lioness with large, ferocious eyes. The eyes were not human, but Jemu thought he detected something familiar in them, and this familiar quality quieted his natural fear enough so that he could approach her.

And in the light of day, Ralla and Jemu rode like a storm into the Sumtur capital.

* * *Diane Gallant has had stories published in Nova SF, Revelation, The Leading Edge, Dragons, Knights and Angels, and she has upcoming stories in MindFlights and Aoife's Kiss. She lives in Pennsylvania.

What do you think is the attraction of the fantasy genre? I think that while Fantasy is set in unknown and magical lands, at the same time it speaks to beauty and the truth of the heart.